Composite fibre reinforced plastic (FRP) materials have been used in boat building for over 50 years. The first boats produced in fibreglass and polyester laminating resin using the hand lay-up process date from the 1970s.

The increased use of composite materials as a result of their ease of transformation, which workers can learn in just a short time, has been limited only by its close dependence on the cost of producing models and moulds. These problems have not, however, prevented the spread of their use on a global scale. In the last 15 years the production of FRP boats has developed to such a degree as to achieve results that just a short time ago were inconceivable. To a large extent, this development can be explained by the introduction of raw materials with increasingly high-performance mechanical features.

The main spin-offs and innovations in the boating and naval sectors, in the form of new construction materials and technologies, are a result of the experience gained since the post-war years first in the aeronautical and then in the automotive sector. In these sectors – which for all countries are economically strategic since they are closely linked to civil transport and mass production – the development of high-performance materials has been the focus of highly expensive tests and trials. In the boating sector, however, these are not possible, as it does not have the mass production element that would justify the costs.

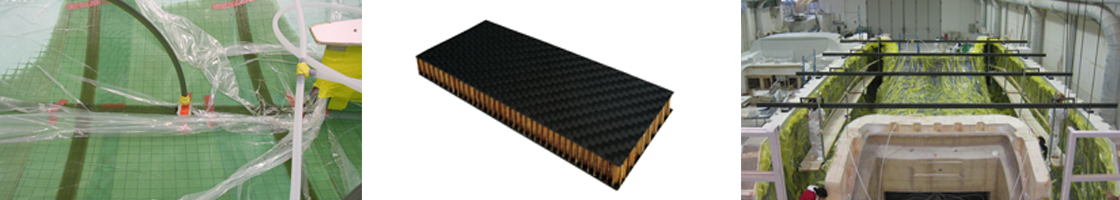

Several years have gone by since the carbon fibres that today are a very real alternative first appeared in the boating world, including for the construction of small and medium-sized components such as hatches, gangplanks, stern doors and garage doors. The choice of carbon in place of aluminium makes it possible to achieve a notable reduction in weight and a 40% increase in strength. This in turn makes it possible, for example, to use less sturdy, i.e. lighter, fittings and lifting mechanisms.

Carbon is the material of choice when there is a need to use support structures with critical rigidity features and to reduce weight and maintenance-hours.

Carbon fibre has replaced many other materials commonly used in high-technology sectors. That is the case in the nautical sector too, where developments in construction techniques, and so in the ways these fibres are processed to obtain the final product, have enabled their use in the production of leisure, competition and commercial craft.

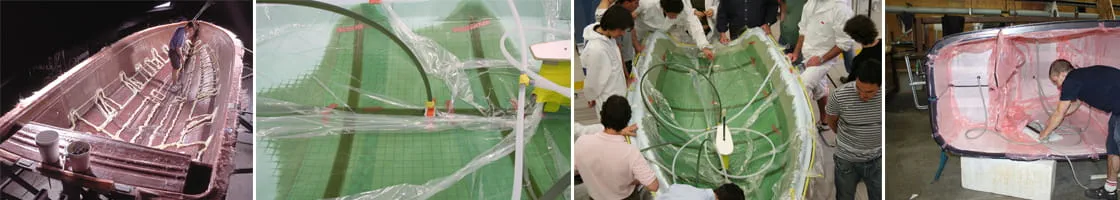

The introduction of carbon and polymeric matrices with advanced mechanical properties has revolutionised the production process. Boatyards have made the necessary investments, with the support of raw materials producers. Case histories are now available that confirm results that for years were only available through finite element method (FEM) analyses and laboratory tests. The use of advanced composite materials in the boating sector is now well established and composites are used for boats and for parts that are particularly subject to mechanical stress.

One of the multinationals investing most in researching and developing new materials is Gurit: an ideal partner for boatyards aiming to build products with a high technological content. The hull and the bridge, bulkhead, rudder and keel are made of carbon pre-impregnated (pre-preg) with epoxy resin.

And it’s not just regatta-quality boats that enjoy the benefits of using carbon fibre. The need to keep weight down without reducing the vessel’s mechanical performance has led some yards to re-design their yachts by introducing new laminates and new production processes. The Sanlorenza shipyard has revolutionised its yacht-building methods and obtained notable benefits in terms of reducing the weight and improving the quality of the end product. All the superstructures and main decks for a large number of production lines are made using full carbon infusion. Italy is Europe’s third producer of composite materials and has been involved in research into and the production and application of composites since the early years of the 20th century.

In recent years, the nautical market has seen a shift towards the production of very large yachts. Customers have become increasingly demanding in their quest for something that truly represents them, so anything that is new and allows them to stand out from the crowd is viewed differently with respect to the past. Until a few years ago the use of carbon was an “exotic” choice. Today, however, it is an added value that people are willing to pay for.

But mega-yachts are just one segment of the nautical sector. The limit, in terms of length and displacement, within which it is technically and economically advantageous to build yachts in composite materials is about 50 metres. Below 40 meters, in cases where the production numbers exist to amortise model and mould costs, nearly all yachts are built in composite materials. Between 40 and 50 meters, customers often opt for metal or hybrid steel/aluminium solutions.

And it is in this segment that the use of advanced composites, high-mechanical-performance carbon fibres and polymer matrices has the greatest potential for expansion. Carbon fibres, processed using well-established processes such as infusion, pre-preg and resin transfer moulding (RTM) are the only real alternative to aluminium. Boatyards that placed their bets on carbon years ago now find themselves at an advantage, since they have gained the know-how and built up the facilities to produce at competitive costs.

In Italy as in other countries, the production of big yachts is entrusted to firms with the necessary expertise. Low-cost producers, which can be found, for example, in the countries of Asia, represent an alternative choice but only for those boatyards that batch-produce small boats. In the coming years a growth in demand is expected, as a result of the lightness and increased energy efficiency of the vessels, and strict environmental rules.

Carbon fibre production is rapidly increasing to cope with market demand. With manufacturing costs gradually falling, raw materials producers are increasing their production capacity. And this will make it possible to introduce lower-cost carbon fibres to the market, while maintaining quality levels.